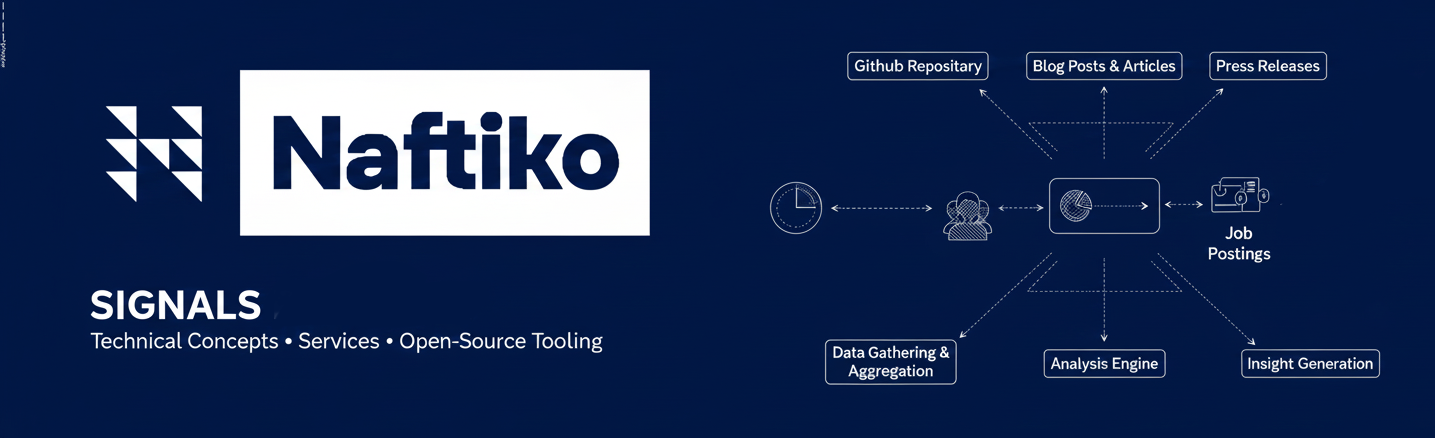

I recently sat down with Fran Méndez on the Naftiko Capabilities podcast, the creator of AsyncAPI, for what turned into one of the most honest conversations I've had in a while. We talked about what happens after you build something successful, the brutal economics of open source, and why he walked away from the project he spent a decade building.

The Accidental Standard

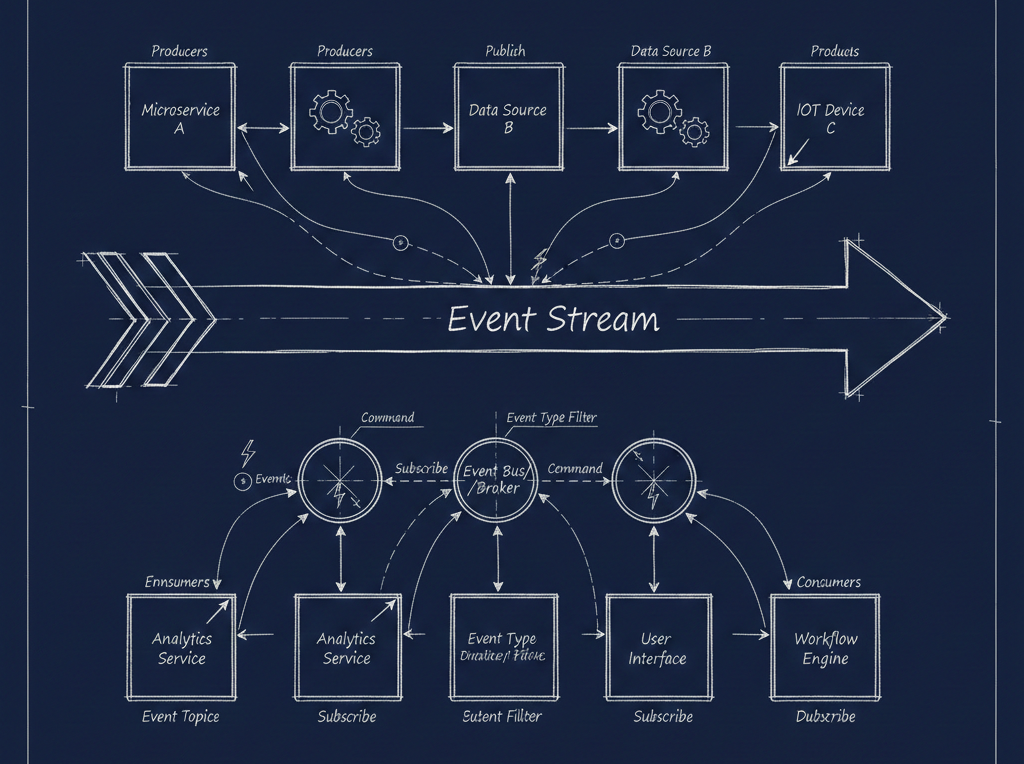

AsyncAPI started the way a lot of good things do—out of necessity. Fran was building event-driven architectures and found himself copy-pasting the same boilerplate code over and over. About 80% of every service was identical. The business logic changed, but everything else—connecting to brokers, consuming from topics, processing messages—was repetitive work.

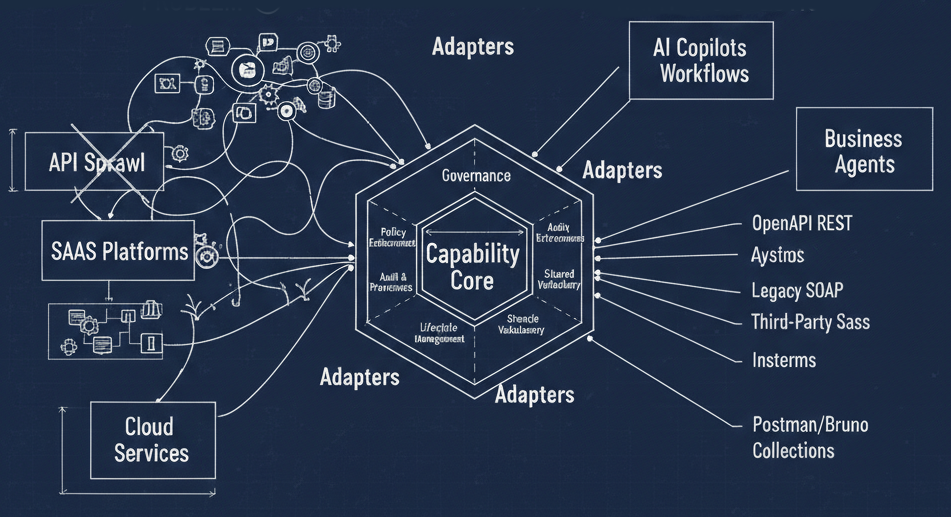

He looked for something like OpenAPI but for events. It didn't exist. So he hacked OpenAPI, treating GET as subscribe and POST as publish. It worked for documentation but fell apart for everything else. Eventually, he forked OpenAPI and started changing what didn't make sense for event-driven systems.

Ten years later, AsyncAPI sits alongside OpenAPI and JSON Schema as a cornerstone of how we define APIs.

The $34 Million Question

Here's the thing about open source success that doesn't get talked about enough: AsyncAPI's calculated value is around $34 million. Fran doesn't have $34 million. He doesn't even have one million.

He was lucky—his words—to work for companies willing to bet on the project. At Postman, he had a team of 12 people at one point. That's rare. Most people working on specs struggle to make half a salary.

The value gets created. The money doesn't follow.

Would it have been different if he'd sold to MuleSoft when he had the chance? Maybe. But then someone else would have created an open alternative anyway. He chose open source because of his ideals about how the world should work, not because of the financial upside.

Running for the Doors

I have this image in my head of tech as a giant warehouse—or maybe a data center—where we all work. The air gets thin. The oxygen runs out. Eventually you have to run for the doors just to breathe.

Some people live in that warehouse permanently and they're fine. Some run out and never come back. I've run out three times now and keep coming back for some reason. Fran ran out this year.

He described it differently: running out the door and immediately lighting a cigarette. Not exactly fresh air—just different smoke.

That cigarette is Commune.

Building for Himself Again

Commune is a social network for newsletters. A headless Substack alternative. But when Fran talks about it, he's not really pitching the product. He's talking about permission.

For years, he did what "the avatar of Fran Méndez" was supposed to do. The AsyncAPI guy. The spec expert. The event-driven architecture person. But when he created AsyncAPI, he wasn't any of those things. He was just someone who liked building stuff and had a problem to solve.

Last summer, he struggled with the disconnect. He wanted to build Commune, but it had nothing to do with APIs. Shouldn't he finish the book? Create courses? Do webinars on event-driven architecture? That's what people expected.

Something clicked. He decided to build what he wanted, not what people expected.

The Savior Complex

There's a trap in open source—and maybe in tech generally—of trying to save people who didn't ask to be saved and don't particularly want it.

Fran spent years trying to make something open, something for everyone. And people, pardon his words, didn't give a fuck. He was solving problems for others that weren't their problems yet. When you're deep in a spec, you're ten years ahead of most people. They're still wondering why any of this is needed.

With Commune, he's trying something different. If it pays his salary, that's success. If someone wants to buy it, he'll consider selling and build something else. He's not here to save the newsletter space. He's here to build something and see what happens.

Why Email Still Matters

Here's something worth thinking about: email is one of the last places where people still have real control.

My wife ran a successful newsletter on Substack. When the platform became somewhere she didn't want to be, she left. Because her audience was email-based, she took them with her to Ghost. Try doing that with your Twitter following.

SMTP and POP are the original APIs. They're decentralized enough. The warehouses haven't fully enclosed them yet. That's why building in the email space matters—not because the technology is innovative, but because the power dynamics are different.

Fran isn't trying to compete with Mailchimp or Kit. He's adding a social layer on top of what already exists. And he's deliberately building something quieter than typical social networks.

On Commune, you can't post unless you have a newsletter. Why? Because newsletter writers can't spam their subscribers with random thoughts. They'll lose them. The economics of email force a certain thoughtfulness that social media economics actively discourage.

Advice for Spec Builders

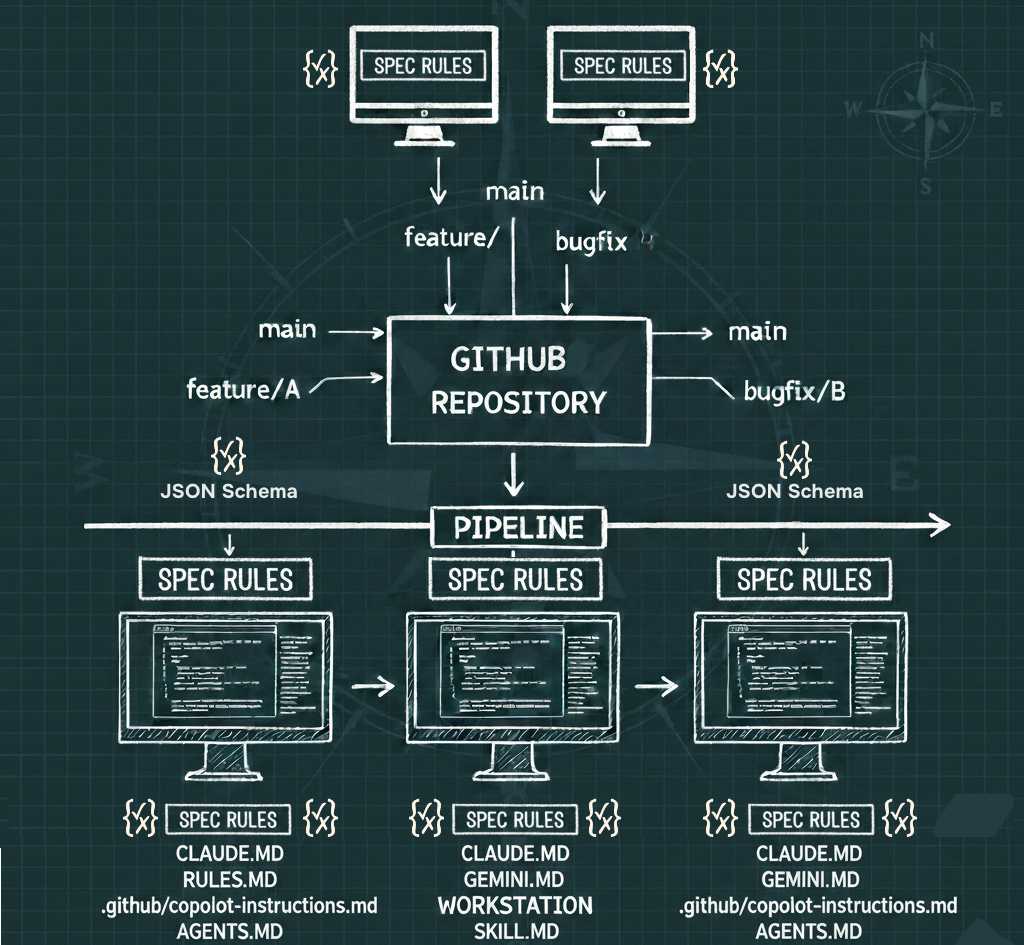

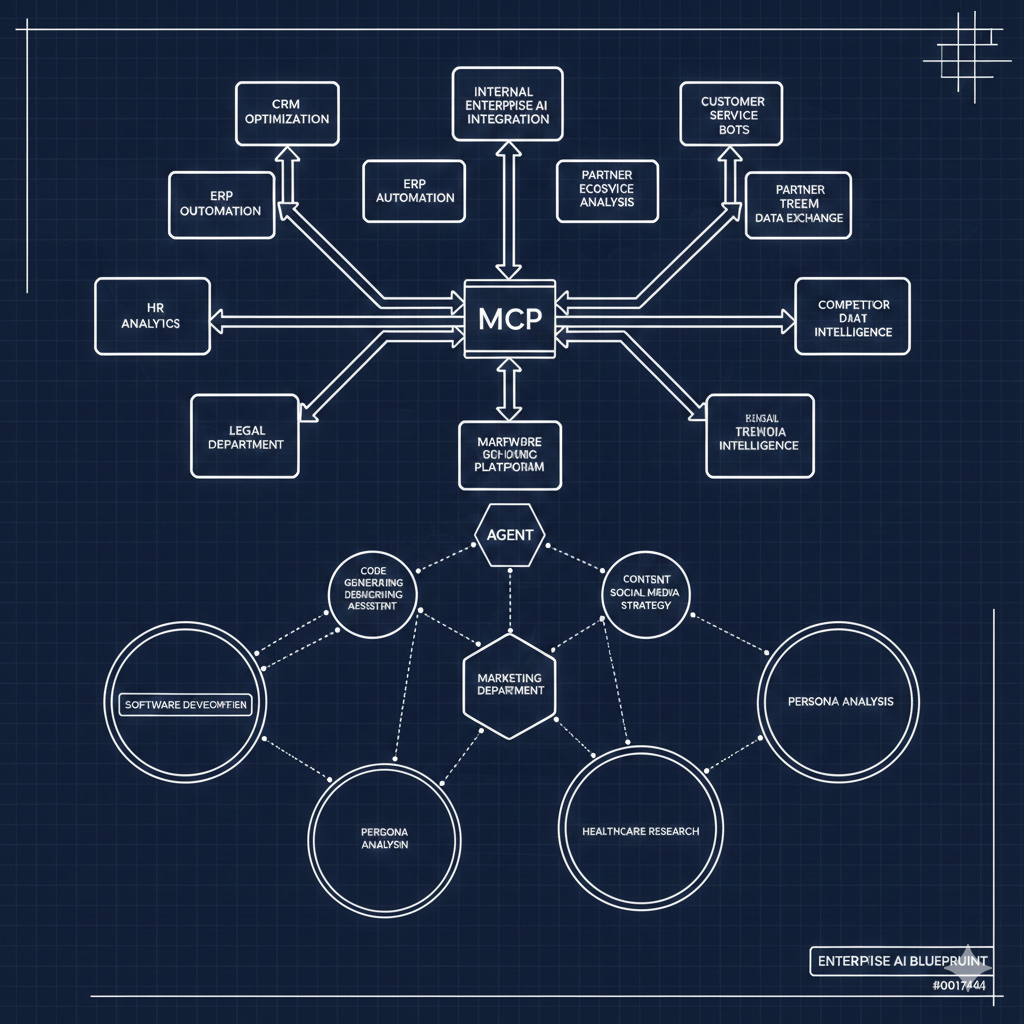

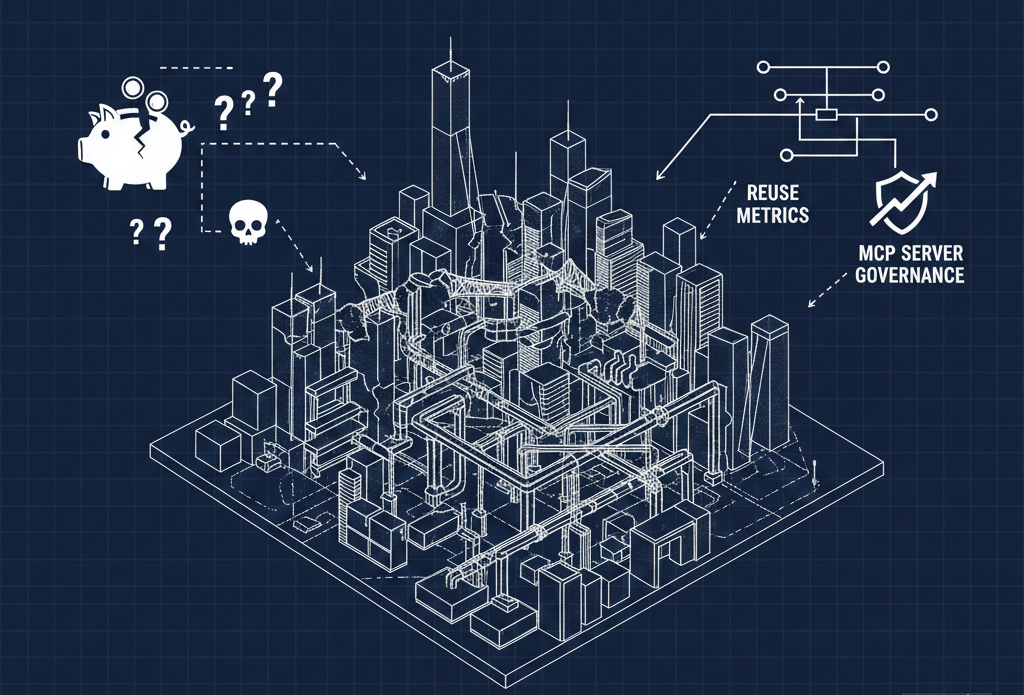

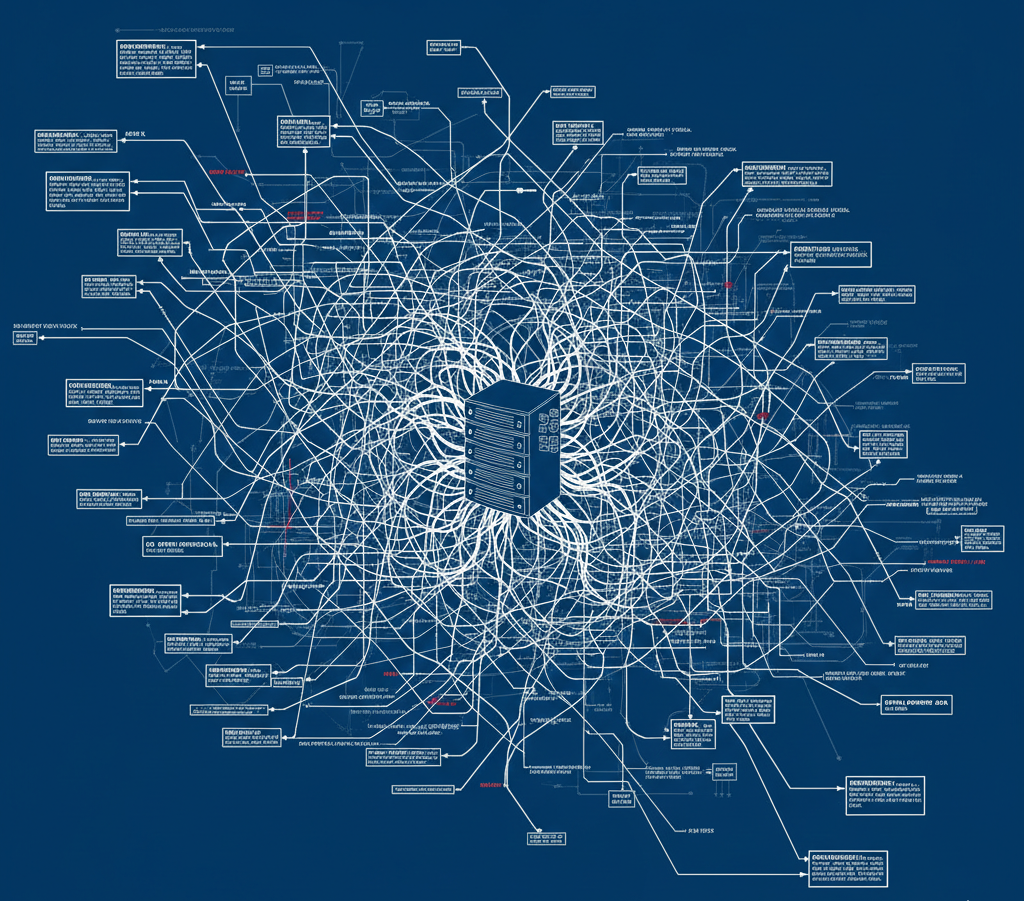

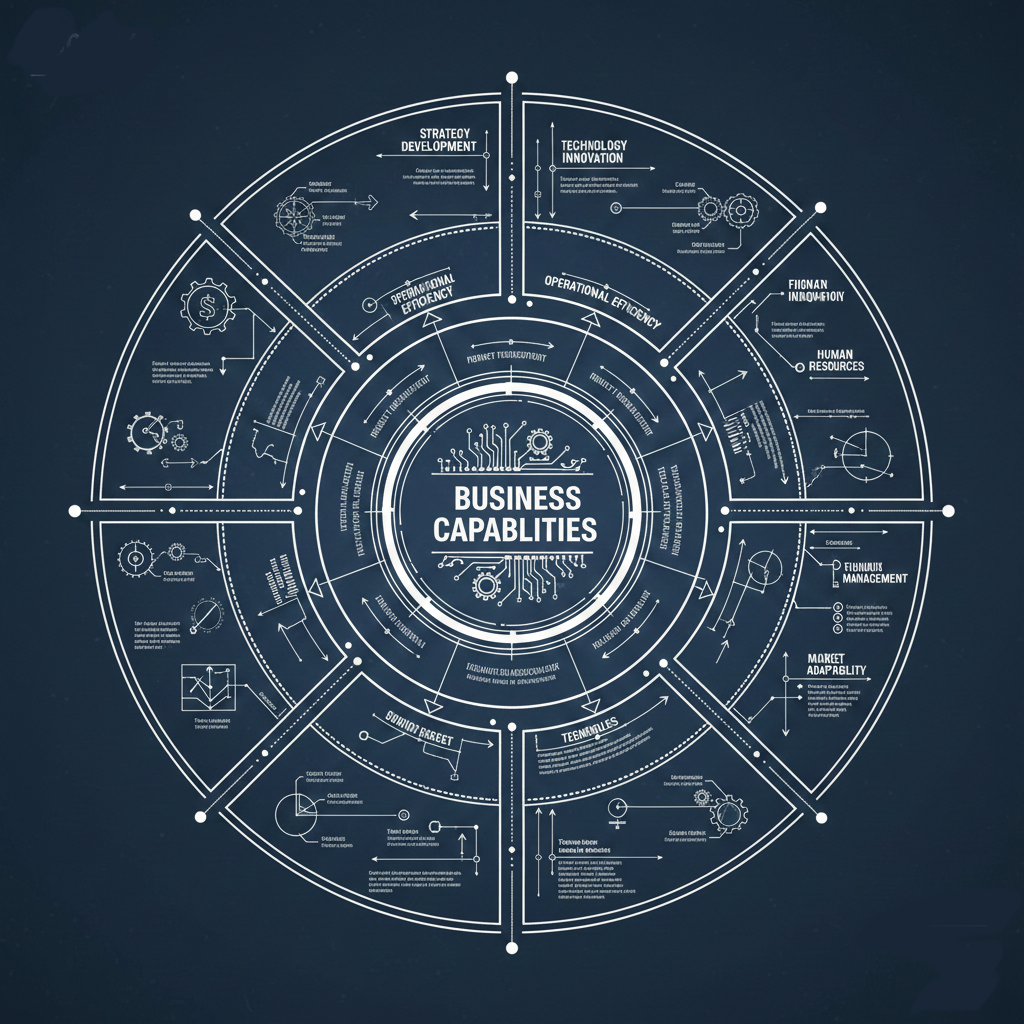

Before we wrapped up, I asked Fran what advice he'd give to people thinking about creating their own spec. We're in a renaissance of specifications right now—AI specs, coding specs, interface specs. I'm reviewing one or two new ones every week.

His answer: start from real use cases that are repeated across the industry, not just because something is possible and cool. Default to having less. It's easier to add features over time than to remove them. Removing things is painful. Changing them completely because you added them too early is painful.

And expect that most people are ten years behind you. They're still wondering why any of this is needed while you're deep in the weeds of version 3.0 features. That's normal. That's the job.

Finding the Signal

I'm not sure what success looks like for any of us anymore. The warehouse metaphor works because it captures how these systems get built around us incrementally, until one day you realize the air is thin and you can't remember the last time you did something just because you wanted to.

Fran seems to have found something in letting himself build whatever he wants. I'm still figuring it out. But I think the conversation matters—not because it has answers, but because it's honest about the questions.

If you're in tech, especially open source, especially if you've built something that grew bigger than you expected, this one might resonate.