As I continue building out API sandboxes for testing and exploration, I’m starting to run into one of those problems that only shows up once you’ve gone a few layers deep. On the surface, it feels small—how do you name your examples in an OpenAPI-driven sandbox? But the more I work through real scenarios, the more I realize this is actually about how we encode business context into our API tooling.

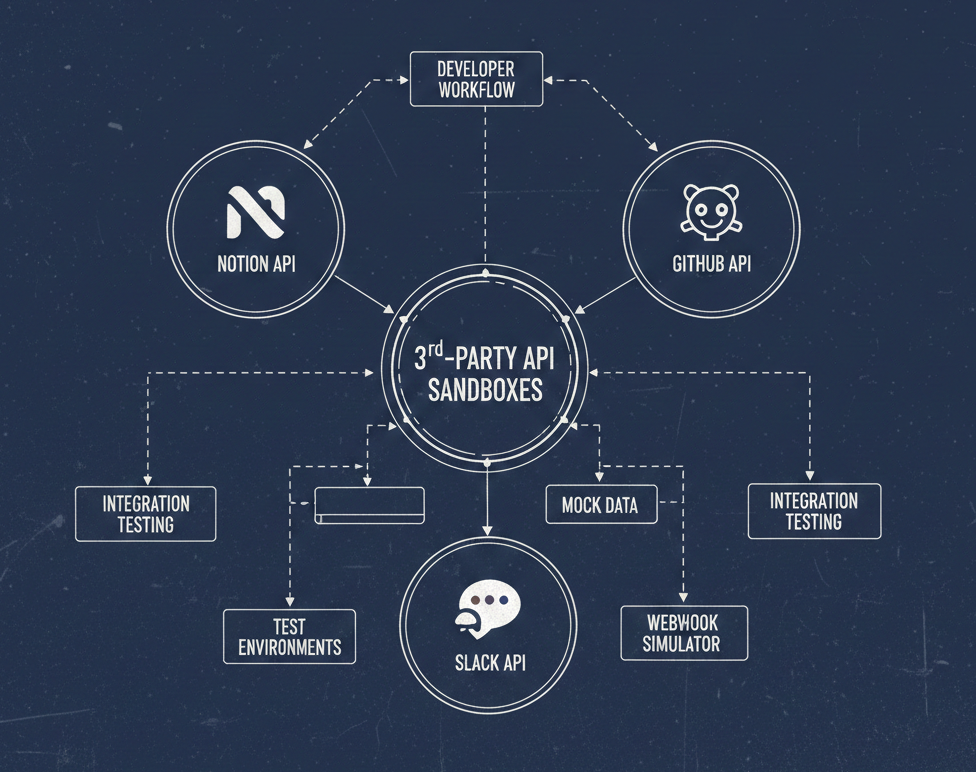

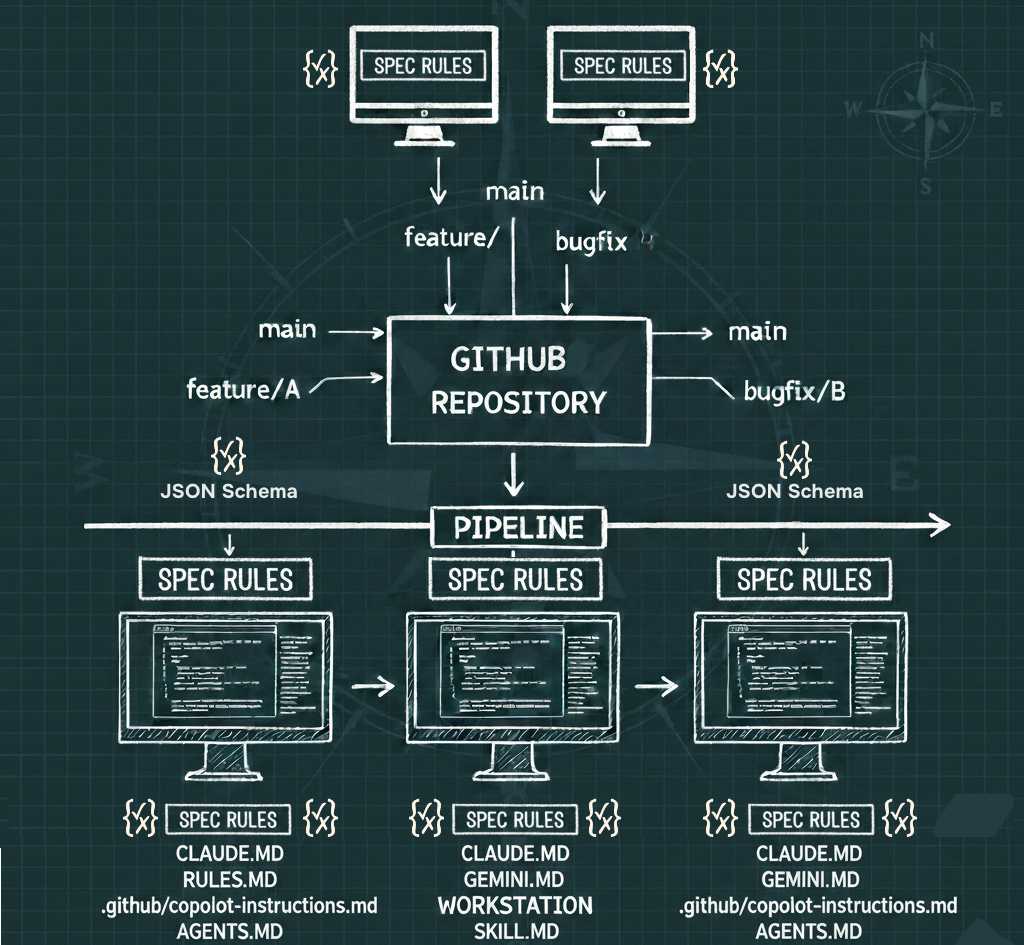

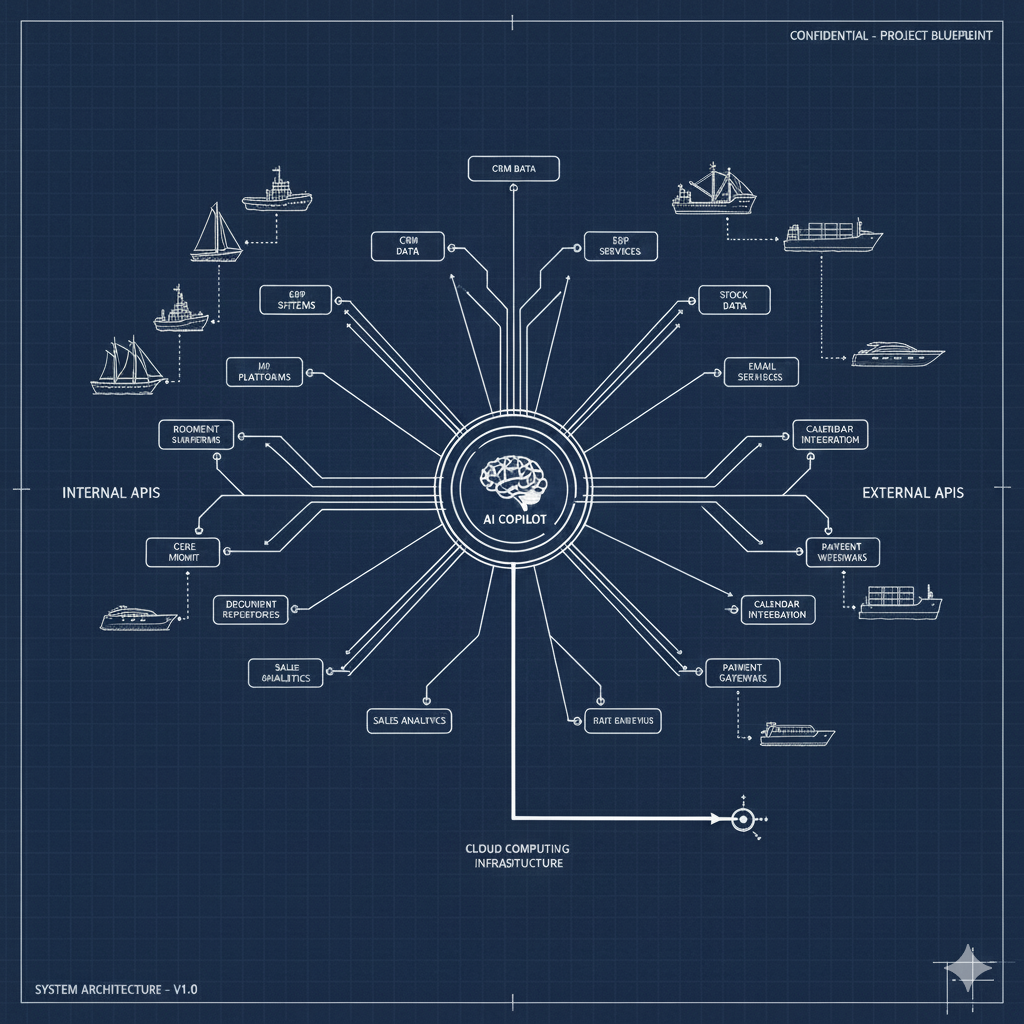

Most of the sandboxes I’m publishing follow the same basic pattern. There’s an OpenAPI at the core. Microcks is used to deploy the mock. Bruno acts as the client. And then everything is packaged up so it can be distributed via Backstage or forked and run locally. This pattern has been working really well across different APIs—GitHub, Slack, Notion, and now some more operational and lifecycle-focused APIs.

Where things get interesting is once you start relying on examples as the primary driver of behavior.

When Simple Mocks Stop Being Enough

With something like the Notion API, the example strategy is pretty straightforward. Each operation has an example request and a set of example responses. Using Microcks extensions, I can negotiate which response gets returned based on headers, parameters, or other inputs. If I want to simulate a successful request, an unauthorized response, or a bad request, that’s easy enough. Each example is clearly tied to a status code and a known failure mode.

That works because the variation is technical. The difference between success and unauthorized is well understood, and the naming conventions almost write themselves.

But as soon as I started working on the APIOps Cycles canvases as a set of mocked APIs, that simplicity disappeared.

Introducing Business Scenarios into the Mock

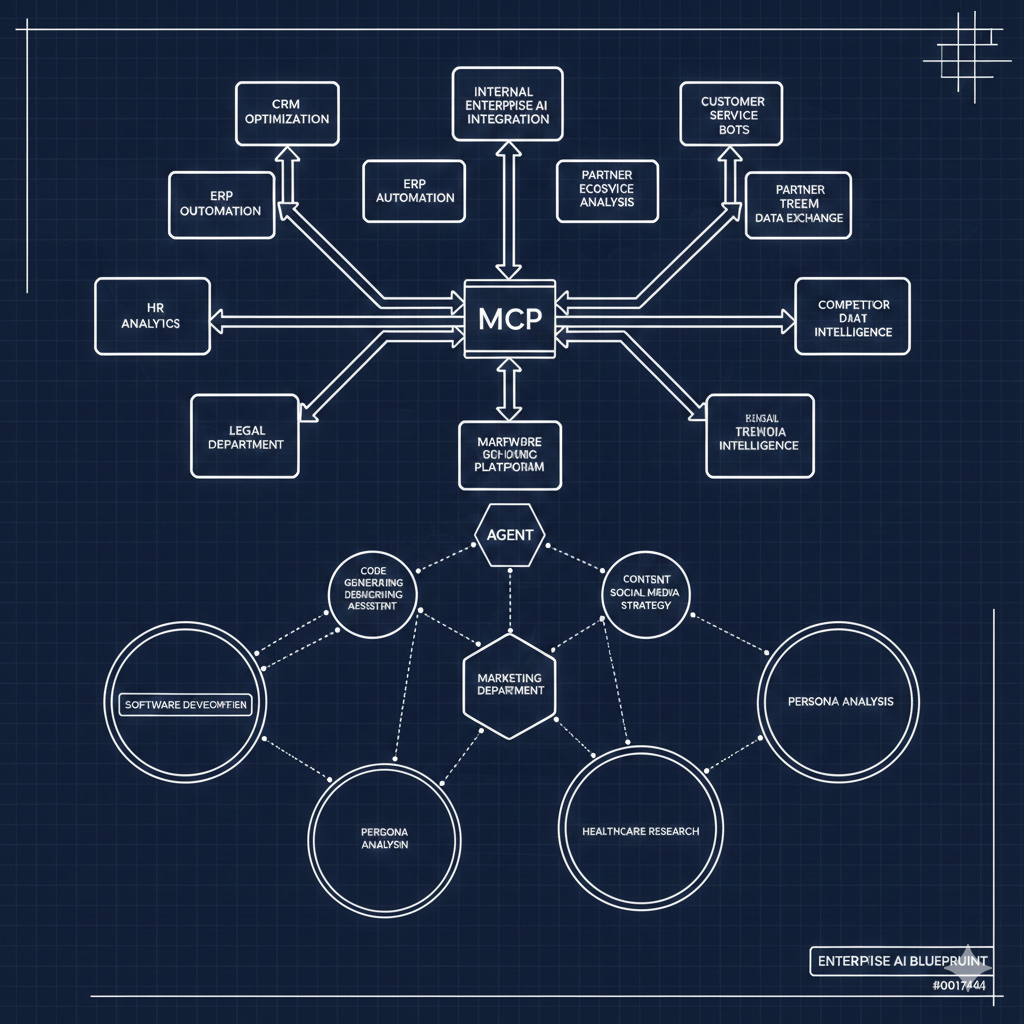

In the APIOps Cycles sandbox, I still have the standard unhappy paths—unauthorized, internal server error, and so on. Those can continue to be negotiated using status codes and problem+JSON examples. No surprises there.

The complication comes from the happy paths.

Instead of a single successful response, I now have multiple valid business scenarios for the same operation. For example, when retrieving a Customer Journey canvas, the response might represent a payments scenario, a shipping and logistics scenario, or an air travel scenario. Each one is a legitimate success response, but each one carries very different semantics and structure.

Using Microcks, I can negotiate which response to return based on an input parameter that indicates the scenario. If I set the scenario to “payments,” I get the payments version of the canvas. If I switch it to “shipping and logistics,” I get that one instead. Technically, this works just fine.

Conceptually, though, I’ve hit a wall.

Naming Examples Is Really About Naming Meaning

Up until now, example naming has been mostly mechanical. “Success.” “Unauthorized.” “BadRequest.” Those names map cleanly to HTTP semantics.

But once examples start representing industries, domains, or business contexts, the naming needs to do a lot more work. Is this example named after the industry? The domain? The capability? The scenario? Some combination of all of them?

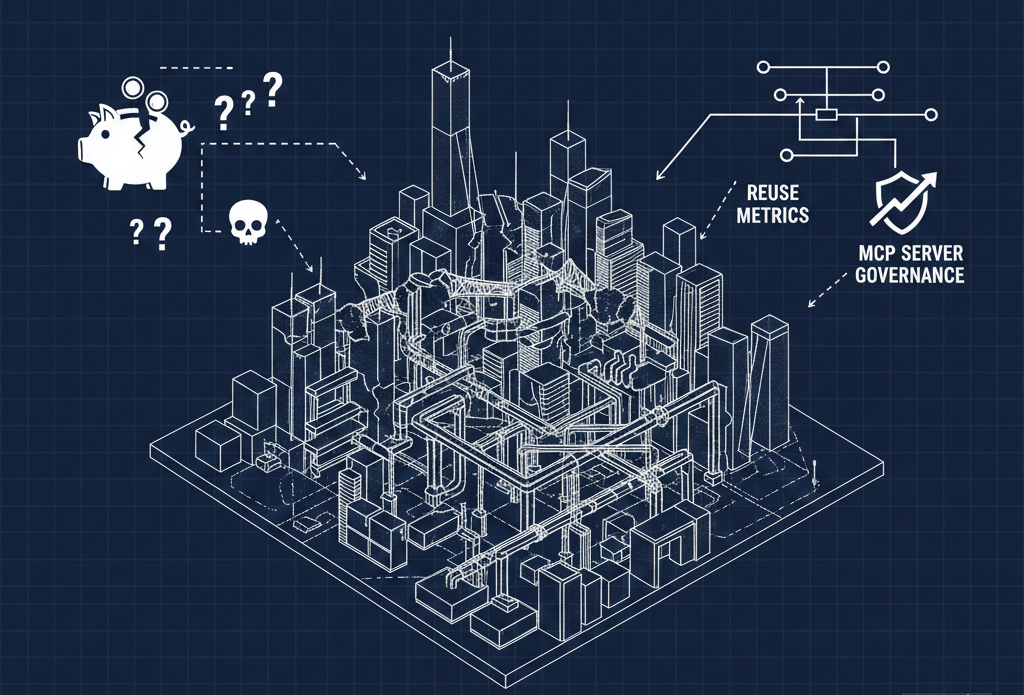

This is where example naming stops being an OpenAPI hygiene issue and starts becoming a modeling problem.

If I’m going to support multiple industry layers or sector-specific scenarios within the same sandbox, I need a consistent, predictable way to describe them. That vocabulary has to make sense to humans, work across tooling like Microcks and Bruno, and remain stable enough that people can build workflows and tests around it.

I don’t think this is something you solve in the abstract.

Learning the Naming by Doing the Work

Right now, I don’t have a finalized naming convention—and that’s intentional. I need to work through more real sandboxes to see where the patterns break down and where they hold. GitHub, Slack, and Notion APIs all bring different constraints. Operational and lifecycle-oriented APIs introduce a different set of challenges entirely.

Only after exercising these examples across multiple domains, industries, and tooling workflows does it make sense to lock anything down as a “standard.”

For now, the unhappy paths are easy. Standard HTTP status codes and problem+JSON give us a solid baseline. It’s the happy paths—the business-specific, context-rich responses—that demand more thought.

Sandboxes as a Place to Work This Out

This is exactly why I keep coming back to sandboxes as a core APIOps practice. They give you a low-risk environment to surface these kinds of issues early, before they get baked into production APIs, governance rules, or platform requirements.

Example naming may seem like a small detail, but it’s one of those details that determines whether sandboxes remain useful learning tools or turn into brittle demos. I’ll keep publishing what I learn as I work through it, but for now, this feels like a problem worth sitting with—and one that’s best solved by doing, not theorizing.

More to come as the patterns start to emerge.